SHORT STORY

HAZLITT AND THE MOBILITY SCOOTER

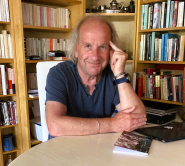

by Ian Forth

‘I spend my time writing Hazlitt’s memoir in which I hope to figure as a sympathetic character, even a friend. Hazlitt was just a dog, but I loved him. Did he feel the same about me, I wonder? I didn’t give him a long or an easy life. But I won’t spend my time plotting revenge. Revenge on who?

I’d dropped into Mehmet’s bookshop one morning to see if he wanted to go to the hammam that evening. Mehmet’s eyes were watery. There was something different about the place.

‘It’s tragic, my friend. I can’t believe it. The old girl gave birth last night.’

I looked around and noticed that the black Labrador that usually dozed on a red and blue kilim by the window was missing.

‘It was too much for her. She farted her last, poor thing. Now, I’ve got two puppies fathered by a backstreet mutt. You’ll take one, won’t you?’

I didn’t know what to say. At my age and in my state of failing health, having a young dog would involve too much responsibility and be sure to end in tears.

‘A dog will help you keep fit and regain your figure,’ Mehmet said. I didn’t appreciate being reminded I was overweight.

On the way home, Hazlitt soiled himself in the taxi. He was stricken with anxiety, yapping at the slightest sound or movement. He fidgeted and gnawed his tail. He soon developed a lopsided gait, for which a vet prescribed steroids.

Before I was afflicted with pain in my spine, I’d always been a keen walker, used to long hikes in the mountains or by the sea. There is freedom in walking; a chance to shed concerns and worries. That sense is enhanced when you’re with the right companion.

I decided that what Hazlitt needed was exercise. Even though my sciatic nerve was being chewed by jagged bone, I’d double my dose of painkillers and grin and bear it. So, each day, we travelled westward on the tram out to the country. Hazlitt, now a giant, was too large to sit on my knee and slid along the gangway as the tram bounced up and down.

On reaching open country, he’d scamper off through the long grass and wildflowers, sniffing for rabbits, foxes, and squirrels and playing peekaboo. He always made sure to bring me a trophy: a stick, some tree bark, a page from a newspaper, an old shoe.

‘I have something for you,’ he’d say, his tail wagging like a metronome.

Hazlitt had a wonderful gift. Even if we trekked along the same path or field, he relished the experience as if for the first time, his sensations never sullied by over-familiarity.

When we stopped for a bite to eat, Hazlitt would lie with his huge front paws stretched out in front of him, his nose moist, his eyebrows twitching at passing insects. As he surveyed the scene, the bustle of the city far away, tranquillity was restored. We passed the time in conversation about this and that.

‘You’ve peed on that same tree trunk more than five times.’

‘I don’t remember. Are you sure it is the same tree as yesterday?’

On reaching home, Hazlitt had to encounter my neighbour’s dog, a hairless thing that looked like a bat; wing-like ears, eyes like black voids, a sausage-shaped trunk and coquettish legs. Bat-dog would launch itself at Hazlitt, circling and yapping. To begin with, Hazlitt enjoyed the social contact with one of his own kind. He was expecting some pleasant small talk, but then the bat-dog would start sniffing his rear, drugging itself on his potent scents, scents that communicated his most intimate secrets. Hazlitt stood unmoving, looking nonplussed.

I’d shoo the dog away, yet each day Hazlitt, like a fool, would trot forward to greet the bat-dog with fresh enthusiasm, only to be horrified by the same indignity.

‘Must I tolerate this?’ he seemed to say.

‘I’ll speak with Mrs Rask. Leave it to me,’ I said aloud.

My neighbour was self-assured with a truculent scowl. We rarely interacted. I’m sure that she looked down on my indolent lifestyle, annoyed by the untidiness of my garden – not improved by Hazlitt’s fly-blown mounds of faecal waste – and the clanking of the wine bottles that I discarded in my recycling bin.

At the time, I knew little about Mrs Rask, and I still don’t know her first name. She beetled off to work early and kept crazy hours, and her bat-dog barked plaintively just before sunset.

I approached her in my dressing gown as she was leaving for work.‘Mrs Rask, could I have a word please?’

‘If it’s quick.’

‘It’s about your dog.’

‘Vladimira? What’s the problem?’

‘My dog, Hazlitt, is an introverted soul and …

‘Please get to the point.’

‘It’s awkward to put into words. He wants … er … Vladimira to stop sniffing him.’

‘Sniffing him?’

‘Yes, you know that dog thing where they … Look, I’m fully aware that dogs enjoy that kind of interaction, but Vladimira is way too enthusiastic. Sometimes she inserts her nose right inside. Hazlitt has told me he finds this intrusive and unpleasant.’

She looked at me with a mixture of astonishment and contempt.

‘Your dog “said” this? It actually told you it was “intrusive and unpleasant?”’

‘They may not have been his exact words.’

Mrs Rask remained silent, a weapon she used regularly.

‘It is perfectly normal for dogs to sniff; it’s how they identify each other, how they establish a pecking order. I don’t see why I should intervene. It would be repressive.’

‘I’d like the intimidation of my dog to stop, please.’

Mrs Rask looked me up and down and got in her car without saying a word.

When I returned home, Hazlitt greeted me expectantly.

‘How did it go?’

I wasn’t sure.

With our daily hikes, my back pain became so debilitating that I had no choice but to put myself into a surgeon’s hands. The operation was scheduled to take place at six in the evening. I remember entering the operating room on the trolley, the air of purposeful activity surrounding me; the clink of surgical instruments in metal bowls, the beeping of machines, the laughter and chatter among the nurses going about their preparations, and then looming above me a huge, masked female face.

‘Good evening. I shall be performing your laminectomy. I have carried out this operation many times. I have a sixty percent success rate.’

The surgeon’s commanding manner made me feel child-like. I swallowed hard:

‘If things don’t go smoothly, will someone take care of Hazlitt? I live alone.’

‘Don’t worry. I also have a dog whom I cherish,’ she said.

Although my senses were dulled, something wasn’t right. The surgeon’s voice was familiar. How did she know Hazlitt was a dog? Before going under, it hit me that my surgeon was also my neighbour.

When they took me to the recovery ward, I couldn’t move. The nurse said this was nothing to worry about, merely the effect of the anaesthetic. However, on returning home, while I could straighten my back, I had limited feeling in my legs. Every evening, I stabbed my thighs with a fork to see if there was any sensation. The pain in my lower back was worse, and the Fentanyl made me feel fuzzy and spaced out.

I drowned in self-pity. Hazlitt was forlorn. If I moved or tried to get up, he sprang to life, wagged his tail and looked pointedly at the front door. When I collapsed back on the sofa, moaning and exhausted, his disappointment was palpable. I was unable to leave the house. I could barely let Hazlitt outside to do his business. I looked at him and shrugged my shoulders.

‘My legs need time. I’m in pain. You’ll have to be patient.’

Illness is a solitary adventure. People are sympathetic for a time but become inured to your stories of discomfort and pain. This was true of Hazlitt. He soon got bored of my groaning and sighing. He’d cover his ears and spend his days watching TV, while I imagined hideous acts of revenge on Mrs Rask. I plotted, choking her in a dark alleyway.

‘”Surgeon strangled by a madman.” What do you think?’

Hazlitt was unimpressed.

‘Too tabloid.’

‘Shards of glass sprinkled in Vladimira’s dog food?’

‘Too Lucrezia Borgia.’

‘Vladimira micro-waved and served in a pie?’ Hazlitt shrugged and went back to watching A Place in the Sun.

Over the months that followed, because of a diet of crisps, chocolate, and sausage rolls, he started putting on weight. His stomach bulged, his face became round and bloated, his limp aggravated. His bark, once loud and booming, had shrunk to a half-hearted ‘woof’. Hazlitt retreated within himself.

I’m ashamed to say that his laziness and inertia started to get on my nerves. He refused to move over when I wanted to sit down, and if I changed the TV channel he growled his disapproval. If I tried to drag him outside to walk in the garden, he refused to budge. I was tired of brushing his hair from the sofa. The house developed a pong of dog and despair.

Then, while browsing on the internet, I saw an advertisement for a mobility scooter. I kicked myself for not having thought of the idea before. A scooter might allow us both to get out of the house, so the next morning I phoned and ordered a Gerryabout 480 XL.

Aha! It’s the scooter! Hazlitt sniffed it suspiciously. He was dubious about this alien, mechanical presence with its factory smells. He was perplexed by the new enthusiasm in my voice as I stripped away the wrapping, revealing the gleaming plastic and metal body. While I checked out all the controls and buttons, Hazlitt withdrew into a corner and sulked.

I went for a trial run. There was nothing too complicated about the tiller control; forward and reverse lever, speed controls, lighting switch for full beam and dipped headlights. I was over the moon. For the first time in ages, I was in motion and able to focus on the sights and sounds around me instead of thinking about my pain. I turned down the speed adjustment dial so Hazlitt could keep up. I imagined we would be like our old selves, not niggling and annoying each other, but side by side, out in the fresh air each day, chatting happily about life.

I decided on an excursion, something that would enthuse Hazlitt and wake him from his torpor. There is a small square of green space about two kilometres from the house. It used to be part of a large manor house estate that had been absorbed by the sprawl of the city. There are mature oak, chestnut, and pine trees that offer shade in the sweltering heat of summer. It is a place where, in the evenings, local residents congregate and chat on benches under the orange glow of street lamps.

That evening, I took a fistful of Fentanyl and put Hazlitt on his lead. He whimpered. I didn’t bother to cajole him, I just dragged him hard, pulling with both hands. It was like moving a rain-soaked mattress. I attached his lead to the scooter seat.

As we were leaving, we met Mrs Rask walking with her dog along the shared gravel pathway between our houses. The surface caused my scooter to wobble.

She skipped forward to the gate.

‘Allow me.’

‘I’m capable of opening it myself, thanks.’

‘I just thought I’d save you the trouble of getting off your scooter. You looked unsteady.’

‘I’m not a complete cripple. Despite your best efforts,’ I muttered, winking at Hazlitt, who wasn’t impressed by irony.

Mrs Rask marched off.

The journey to the square was long and painful, although I enjoyed the responsiveness of the scooter and its swift acceleration. I let the machine tug Hazlitt forward. He was stubborn, but I wasn’t going to give up. Although I worried the scooter might capsize with the uneven load, I was determined to get Hazlitt fit again. Sometimes drivers in the passing traffic stopped to point and laugh hilariously at the sight of an old man on a mobility scooter with a fat dog traipsing behind.

‘We made it,’ I said, opening the iron gate to the square. I was aware but failed to fully realise that Hazlitt was panting heavily and wobbling like a drunk. He limped off, his brain enthusiastic, his body resisting, but for a few seconds, he seemed content to be in the warm outdoor air.

The scene before me started to swell and contract, an effect of the Fentanyl. A group of men in vests and shorts sat smoking, women with hennaed hair leant together conspiratorially. I could make out Mrs Rask sitting alone on a bench, knees close together, bony fingers entwined on her lap, stubborn chin jutting forward.

I heard a noise; in the shadows, a pack of untethered, over-excited dogs roamed the square; large and hairy, small and bald, overweight and barrel-chested, others with short stumps and stomachs scraping the ground, faces turned in on themselves, elongated jaws. Mrs Rask’s bat-dog was the leader of the pack.

It wasn’t long before they noticed Hazlitt — distracted by smelling a flower — and circled round him; taunting, sniffing, nibbling, mounting. Hazlitt froze. I was exasperated by his passivity and his acceptance. After all, he was a large dog.

‘Snarl back, Hazlitt. Show some savagery!’ I shouted.

He stared at me with a look of reproach. I couldn’t bear the sight any longer, so I flashed the headlight of my mobility scooter at full beam on the horror show of deformities. It didn’t have any effect apart from illuminating a swarm of red eyes. I stepped off the scooter, and stumbled over to the mob, kicking out blindly. I felt a stab of pain in my back, but I must have landed a considerable blow because the bat-dog went sailing into the air letting out a wounded screech. It flew high up over the canopy of a large umbrella pine. The spectators stared with open mouths, waiting for what seemed an eternity for the dog to return to earth.

‘My Vladimira! What have you done with her? ’ Mrs Rask shouted from the shadows.

Some of the men got up and walked towards me. I sensed the scene was about to burst into violence.

‘Come on Hazlitt. Let’s get out of here.’

I got back in the saddle and turned the speed dial up to maximum and exited the park. I felt the evening breeze on my moist forehead. I was sailing. On straining around, I could see Hazlitt trailing after me, struggling to keep up and getting further behind. His gentle face looked up.

‘Go ahead. I’ll catch up.’

The next time I looked, Hazlitt was nowhere to be seen. Feeling nauseous, I turned back along the road. Where was he? Had he been dragged back into the park by the pack? What had I done? I then saw the bundle of fur collapsed on the pavement. Unmoving, Hazlitt lay on his side, one paw covering his eyes, his big head flat, his body lifeless. It had been too much for his heart.

Somehow, I had to carry my friend home. I managed to clasp my hands around his chest with my nose brushing his coat. Despite the weight and the pain, I walked slowly home, leaving the scooter behind.

I learned later that the bat-dog had survived with a broken leg and various abrasions.

‘And where is your dog? I haven’t seen or heard him for some time,’ Mrs Rask asked.

I swallowed and turned away.

As I write these words, I notice some of Hazlitt’s gifts from our walks in the corner of the room, an old trainer, a well-chewed stick, the jawbone from a squirrel. Mehmet suggested I find a replacement dog, but my sorrow is too great. I don’t trust where my grief might lead me.

Connect with Ian Forth on X (former Twitter)

Ian Forth used to be an academic but now writes. He has published a family memoir Water Under the Bridge: Recollections From an Only Life, a collection of stories for children ‘Shoelace Saves the Day & Other Stories and a self-illustrated book: Cycling in the Canal des Deux Mers. His short story ‘Leaf Relief’ was published as a podcast on Yorick Radio Productions/Scintillating Stories in June 2023.

His short story ‘Squirrel’ is to be published in The Mocking Owl Roost later this year.

Ian lives in France and Wales.

Please don’t forget

to support the writer!

Tell us your thoughts

Share this page

Visit Ian

Choose Your Next Read

Author Spotlight:

Creative Non-Fiction by Evan Griffith

Author Spotlight:

Rant of Appreciation by Evan Griffith

Author Spotlight

Interview: Evan Griffith

Poetry:

My Poetic Soul

Poetry:

In the Thick of Life

Poetry:

Seasons of Gratitude and Hope

Poetry:

From the Depths of My Thoughts

Poetry:

The Rejected Soul

Poetry:

Dark Hours

Poetry:

The Nameless, Placeless

Poetry:

When the Rain Comes

Poetry:

In My Life

Poetry:

Winter is a Careful Nurse

Fiction:

It Rained That Night

Fiction:

Where Equality Reigned Supreme

Fiction:

Hazlitt and the Mobility Scooter

Fiction:

Slow Drip of Water

Fiction:

Gryphon Bay

Insights:

Almost Lost Forever: A True Story of Love and Survival

Insights:

Gratitude: A Work In Progress

Book Review:

In Search of a Salve: Memoir of a Sex Addict

Book Excerpt:

The Quantum Entanglement Party

A Writer’s Life:

John Steinbeck

Picture Prompt:

A Spectral Harmony

Share Your Thoughts